Making sense of the many names for women’s reproductive aging by Dr. Jerilynn C. Prior

Jerilynn C. Prior BA, MD, FRCPC, ABIM, ABEM is a Professor of Endocrinology and Metabolism at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, B.C. She is the founder (2002) and Scientific Director of the Centre for Menstrual Cycle and Ovulation Research(CeMCOR).

The process of aging of women’s reproductive system, like puberty and most biological transitions, occurs in a generally standardized but variable way and over many years. Also, there are broad age ranges at which we consider something normal or not. Then add on top of that cultural presuppositions, chief among them that “menopause means estrogen deficiency” (rather than that menopausal estrogen and progesterone levels are normally low), and we have real confusion and a situation that is not helpful1 for women or for their communication with health care providers.

I will do my best to describe some of these standardized ways that women’s physiology changes during reproductive aging. I will mention the current terms and the words that have some physiological relevance and should be used. Because I am a physician, I believe that understanding of “the story” of life phases and the “why” of experiences is helpful. It is also necessary to appreciate the whole woman in her social, cultural, physical and experiential environments markedly influence her experiences.

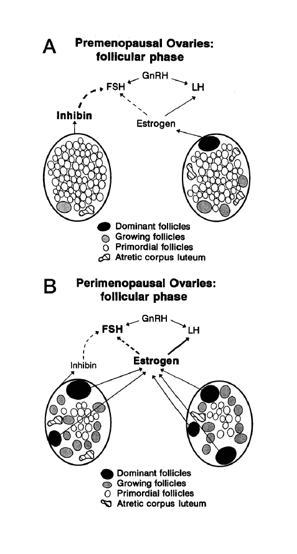

After extensive research to understand mine and my patient’s puzzling midlife experiences, I learned that the ovaries start to make less Inhibin (really Inhibin B) while cycles are still regular2;3. Inhibin is small hormone made in the follicular cells surrounding stored eggs; its job is to control levels of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH). Because FSH stimulates follicles to grow, Inhibin is necessary to limit the number of stimulated follicles and to prevent us having litters. As shown (Figure below), by very early perimenopause there are fewer remaining ovarian follicles (B), Inhibin is decreased and this allows higher FSH levels and more stimulated follicles. Since each recruited follicle makes some estrogen, levels rise and the higher estrogen levels are also not reliably able to control FSH3.

Legend: The ovaries are shown as a stylized oval with follicles in various degrees of maturation. A. shows what is occurring in the follicular phase of a premenopausal ovary; B. illustrates the normal changes that occur in perimenopause. Reprinted from Prior Endocrine Reviews 1990

The same normal reproductive aging pattern of lower Inhibin, higher FSH and estrogen occurs when the ovary is injured; this can be by chemotherapy or radiotherapy for cancer, partial removal, more rapidly than normal after hysterectomy or tubal ligation/removal and in those with immune or genetic problems. The chaos of women’s reproductive aging occurs for these Inhibin-related reasons but also because the hypothalamic-pituitary ovarian feedbacks are disrupted (so a normal midcycle estrogen peak may not trigger the luteinizing hormone (LH) peak or the LH peak may not stimulate ovulation4). An FSH level, even one that is taken on cycle day 3, is not diagnostic of perimenopause. That estrogen levels average 20% higher in perimenopausal than in premenopausal women 3, I learned from a systematic review of studies within each of several centres; but symptomatic women may have double or triple normal cycle phase-specific levels that create the “perimenopausal ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome” because this situation resembles an adverse effect that may occur in IVF 3.

With this understanding we can define the three terms for normal reproductive life phases, the term used for perimenopause or menopause that comes too early and also identify some inappropriate labels.

Premenopause is the entire time (usually 30-40 years) from the first menstruation (menarche) until the changes of perimenopause start.

Perimenopause begins when cycles are still regular (called very early perimenopause and this phase lasts 2-5 years) but an observant woman notices typical experience changes5. Because the current official classification of reproductive aging begins with irregular cycles6, no one knows at what age on average this may start; likely it is normal from as young as age 35. At least three of nine typical experience changes, especially the start of night sweats, sleep problems or heavy flow, can be used to determine that you have begun this phase5. Additional potential perimenopause changes are: increased cramps, increased premenstrual physical and emotional unwanted experiences, shorter cycles (usually ≤25 days), increased or new breast tenderness, increased or new migraines and weight gain without important changes in exercise or food intake7. Perimenopause’s early menopausal transition starts when cycles become irregular and lasts a year or so; the late menopause transition begins with the first skipped cycle (60 days without flow) and late perimenopause is the year after the last flow.

Menopause is the life phase that lasts from a year after the final flow for the rest of women’s lives. It is normal for both estrogen and progesterone levels to be low. Hot flushes/flashes and night sweats may continue for many years but heavy flow, cramps, breast tenderness, premenstrual-type symptoms and severe migraine are usually gone. (The term “postmenopause” is sometimes used interchangeably with menopause but is double-speak and refers to an erroneous use of the word “menopause” to mean the literal final menstrual flow).

Primary Ovarian Insufficiency means that the typical changes of perimenopause begin at less than 35 years of age, or that menopause comes early (at less than age 40)8. If a woman with what is usually called primary ovarian failure isn’t diagnosed before she has been a year without flow it means she has already endured distressing years of mysterious menstrual cycle, hot flush/flash and night sweat and mood changes without support. Primary ovarian insufficiency is a better term because “failure” is very negative and doesn’t reflect the variable cycles of POI and ovarian aging that occurs with the hormonal and experience changes of perimenopause. It is also better than calling it early menopause since it begins with perimenopausal experiences.

Throughout the month of April, re: Cycling will be posting about the broad range of experiences related to women’s reproductive aging.

Reference List

(1) Prior JC. Perimenopause lost – reframing the end of menstruation. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 2006; 24(4):323-335.

(2) Robertson DM, Hale GE, Jolley D, Fraser IS, Hughes CL, Burger HG. Interrelationships between ovarian and pituitary hormones in ovulatory menstrual cycles across reproductive age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 94(1):138-144.

(3) Prior JC. Perimenopause: The complex endocrinology of the menopausal transition. Endocr Rev 1998; 19:397-428.

(4) Weiss G, Skurnick JH, Goldsmith LT, Santoro NF, Park SJ. Menopause and hypothalamic-pituitary sensitivity to estrogen. JAMA 2004; 292(24):2991-2996.

(5) Prior JC, Seifert-Klauss VR, Hale G. The Endocrinology of perimenopause – new definitions and understandings of hormonal and bone changes. In: Dvoryk V, editor. Current Topics in Menopause. Bentham Science Publishers Ltd; 2012. 54-83.

(6) Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, Lobo R, Maki P, Rebar RW et al. Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop +10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. Climacteric 2012; 15(2):105-114.

(7) Prior JC. Clearing confusion about perimenopause. BC Med J 2005; 47(10):534-538.

(8) Rafique S, Sterling EW, Nelson LM. A new approach to primary ovarian insufficiency. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2012; 39(4):567-586.

Thank you Jerilynn for a clear and sensible description of the process. I’ll be sharing it with my students.