Peggy Stubbs and Evelina Sterling advocate for comprehensive menstrual education

For nearly forty years, the Society for Menstrual Cycle Research (SMCR) has been promoting the perspective that the menstrual cycle is central to girls’ and women’s overall health. But this connection seems to be nearly invisible to the public, and even in the public health arena. A recent informal, but telling, series of Internet searches reveals that many agencies provide minimal or no information about the menstrual cycle. This information deficit was discussed at SMCR’s June 2015 conference in a session offered by Evelina Sterling, Heather Guidone, Diana Karczmarczka and Peggy Stubbs. For example, the menstrual cycle is not listed in the Healthy People Goals, and so is not seen as a priority by groups such as the CDC. Instead, the prevailing attitude seems to be that other public health issues are more important and that, beyond basic biology and management, girls and women (and boys and men) don’t need to know much more about the menstrual cycle. Menstruation, from menarche to menopause, is not presented as an integral component of women’s health. Menstruation is not associated with long-term health and wellness, nor is it considered as relevant to the experience of specific illnesses, disabilities or mental health conditions.

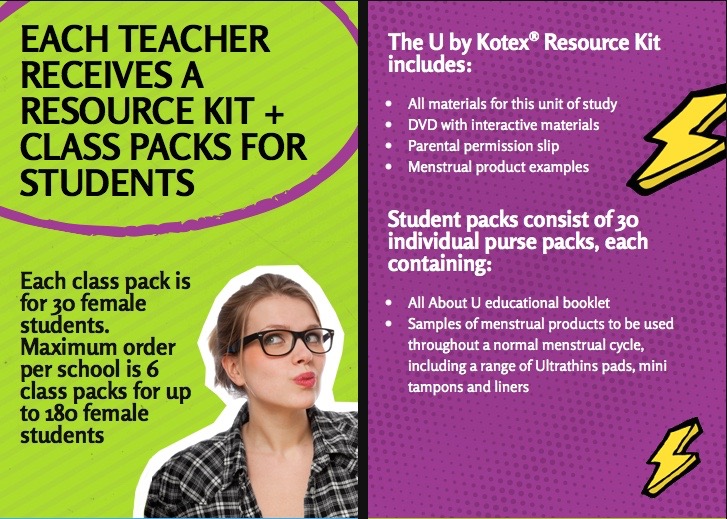

Menstrual product companies fill a public health gap by providing menstrual education materials to schools.

The public health gap in menstrual education has been filled by menstrual product manufacturers whose materials are used in many schools and whose online presence is influencing what girls first learn about menstruation. While menstrual management is of great importance, and while we applaud recent efforts by some product manufacturers (e.g., Kotex) to address and try to reduce menstruation stigma, so much more could and should be done to help girls and women learn about how the cycle serves as a “vital sign” of health, as opposed to what too many consider a normative but inconvenient at best, debilitating biological necessity.

We think a coalition of biomedical public health and psychosocial researchers promoting menstruation as a vital sign, and countering one of today’s most facile conceptions of menstruation—that it is a lifestyle choice—can do much better.

While we appreciate there are many public health issues relevant to girls’ and women’s health, we believe it is time for menstruation to take center stage, to be more broadly considered in relation to women’s lives and well-being. SMCR researchers and others have long promoted a comprehensive, lifespan approach to menstrual education, one that is both broad and deep, and features the interconnection of its biological and psychosocial aspects. This means addressing the connections between our biology and what we (both as individuals and as a culture) think about it and do about it.

This means moving beyond a nuts and bolts approach to menstruation, whatever the age group, not forgetting to include boys and men in our efforts. This means that all educators—family members, teachers, public health workers, product manufacturers, health care providers and the like—should strive to learn about and convey how the cycle influences well-being. This means consulting not only the latest biomedical research but also the treasure trove of social science research on the topic. Educators can begin with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) 2015 paper (1) on using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign in the education of young girls and adolescents. AGOC researchers have also provided guidelines for health-care providers about how to take a menstruation history and how to help parents convey information about menstruation to daughters (See Hilliard, 2014) (2). In addition, educators should study the many papers and presentations by SMCR researchers and other scholars to learn how psychosocial aspects of the cycle can impact such things as self-image and sexual-decision making. (e.g., Stubbs, 2008; Erchull, 2002, 2015; Johnston-Robledo, Stubbs & Walch, 2013) (3).

Our challenge is to make collective and collaborative use of this material, thereby helping the public to think about menstruation—from menarche to menopause—as a window into well-being instead of an experience simply to put up with. Providing full disclosure about the cycle, weaving its complexities into education programs without overcomplicating or unnecessarily alarming audiences, will require ongoing work. But knowledge is power and girls and women deserve nothing less.

1. Committee Opinion No. 651. (2015). Menstruation in girls and adolescents: using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 126:e, 143-146.

2. Hilliard, P.J.A. (2014). Menstruation in Adolescents: What Do We Know? and What Do We Do with the Information? Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 27(6), 309-319. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2013.12.001

3. Stubbs, M.L. (2008). Cultural perceptions and practices around menarche and adolescent menstruation in the United States. Annals of the New York Academy of Science, 1135, 58-66.

Erchull, M.J., Chrisler, J.C., Gorman, J.A. & Johnston-Robledo, I. (2002). Fact or fiction: A content analysis of educational materials about menstruation. Journal of Early Adolescence, 22, 455-474.

Erchull, M.J., & Richmond, K. (2015). “It’s normal…Mom will be home in an hour”: The role of fathers in menstrual education. Women’s Reproductive Health, 2, 93-110.

Johnston-Robledo, I. Stubbs, M.L. and Walch, A. (2013). Oxford Bibliographies in Childhood Studies. Menstruation. www.oxfordbibliographies.com

Margaret L. (Peggy) Stubbs is a professor of psychology at Chatham University in Pittsburgh, PA, and a member of re: Cycling’s editorial board. Her areas of expertise include psychosocial aspects of menstruation; attitudes towards menstruation, pubertal development; and menstrual education throughout the lifespan.

Evelina Sterling is a lecturer of sociology at Kennesaw State University and a public health researcher and medical sociologist focusing primarily on women’s health and reproductive issues.