This post was originally published at re:Cycling on March 27, 2015.

State of Wonder–Part 3: Wondering about menstrual cycle misconceptions in a fictionalized theory for extended fertility

In Parts 1 and 2, I wondered why author Ann Patchett chose not to include information about menstruation, femcare products and birth control that, logically, would have enhanced her novel’s inciting premise—lifelong menstruation and fertility—while retaining the literary integrity of State of Wonder. I believe just a few sentences could have accomplished this.

Now, I wonder about the menstrual cycle misconceptions that underpin Patchett’s proposed explanation for the extended fertility experienced by the Lakashi tribe.

Now, I wonder about the menstrual cycle misconceptions that underpin Patchett’s proposed explanation for the extended fertility experienced by the Lakashi tribe.

The reader learns with Dr. Marina Singh, the novel’s protagonist, that the Lakashi women continue to menstruate, ovulate, conceive and give birth into their 70s because they regularly chew the bark of Martin trees found in the Brazilian rainforest. The bark is so effective there are no post-menopausal Lakashi.

The women chew the bark once every five days except when they are menstruating and when they’re pregnant, because the bark repulses them from the moment of conception. The researchers, led by Dr. Annick Swenson who has been studying the Lakashi for decades, observe the women chewing the bark and collect cervical mucus swabs to monitor their estrogen levels. They dab the swabs on slides for “ferning.”

“No one does ferning anymore,” Marina said. It was the slightly arcane process of watching estrogen grow into intricate fern patterns on slides. No ferns, no fertility.

Dr. Saturn shrugged. “It’s very effective for the Lakashi. Their estrogen levels are quite sensitive to the intake of the bark.”

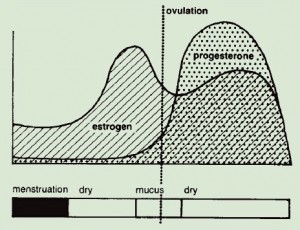

Hormonal changes during the menstrual cycle: Used with permission from Geraldine Matus, Justisse Healthworks for Women

Patchett perpetuates the myth that fertility is all about estrogen. Actually, fertility is dependent upon the cyclic ebb and flow of estrogen and progesterone. As the graphic illustrates, estrogen rises in the pre-ovulatory phase, peaks, then drops dramatically just before ovulation occurs. Post ovulation, estrogen continues to be produced but its effect on cervical mucus is suppressed (no ferns) by the substantially higher level of progesterone which acts upon the endometrium in preparation for pregnancy.

It would make more sense for the Lakashi to chew the bark more often during the pre-ovulatory phase but be repulsed by it post-ovulation as progesterone rises. How neat would that have been? The researchers could have pinpointed ovulation in their study subjects. Oddly, ovulation is not even mentioned.

Furthermore, if intake of the bark raises estrogen levels, chewing the bark every five days would interfere with the post-ovulatory rise of progesterone, throwing the hormonal interplay of estrogen and progesterone required to achieve and support a pregnancy out of whack.

Another issue: Marina is told that by chewing the bark “her window for monthly fertility would be extended from three days to thirteen.” What does this really mean? According to the scientific principles underlying the fertility awareness method of achieving or avoiding pregnancy, the fertile phase starts when fertile-quality cervical mucus is first observed and ends when three dry days have passed. The bark would increase the fertile quality of the mucus and the number of days fertile mucus occurs pre-ovulation, thereby increasing the chances for conception. But sperm can only survive five days, kept viable by the mucus that locks it in the cervical crypts until an egg is released. And that egg will remain viable for only 24 hours. Timing of intercourse still matters. The extended fertility explanation in the novel does not suggest the Martin tree bark has any effect on these accepted reproductive factors.

Am I being too picky? Perhaps. State of Wonder is, after all, a work of fiction. But I expect a seasoned novelist to have researched basic menstrual cycle facts so as not to pose an explanation for extended fertility that doesn’t pass scrutiny. Had Patchett consulted with a menstrual cycle expert, perhaps an SMCR member, she might have imagined a much more plausible scenario. In the actual book I read, there were no acknowledgements to those she may have consulted on the subject.

I loved State of Wonder for all it’s literary complexity that goes far beyond the details related to the menstrual cycle that I have wondered about in this 3-part series. But it’s been fun to explore how one novelist wrote about a subject I am intimately familiar with and to suggest how she might have done it differently.

Thank you Ann Patchett. Here’s to more menstrual mentions in literature.

Laura Wershler is a veteran sexual and reproductive health advocate and writer, SMCR member, and editor-in-chief of re:Cycling.