Guest Post by Jacqueline Thomas

Having entered my Ph.D. program in English already aware of the general need to better prepare girls for menarche, I wrote Lizzy & the Light Below in the midst of my studies to give moms a tool for starting the conversation with their daughters. Based on the anthropological part of my research, Lizzy is a simple Alice-in-Wonderland kind of story about a girl who gets her first period at school one day, takes a shortcut home through the woods, and discovers a magical cave in which a wise old woman named Ciela shares a different story about menstruation than the one she has learned at school. While I kept the story simple and pitched it at preteen girls, I included a preface summarizing the research that underpins its message: Not only is menstruation a natural process that we should not be ashamed of; it is a pillar of human culture that we should take pride in.

Having entered my Ph.D. program in English already aware of the general need to better prepare girls for menarche, I wrote Lizzy & the Light Below in the midst of my studies to give moms a tool for starting the conversation with their daughters. Based on the anthropological part of my research, Lizzy is a simple Alice-in-Wonderland kind of story about a girl who gets her first period at school one day, takes a shortcut home through the woods, and discovers a magical cave in which a wise old woman named Ciela shares a different story about menstruation than the one she has learned at school. While I kept the story simple and pitched it at preteen girls, I included a preface summarizing the research that underpins its message: Not only is menstruation a natural process that we should not be ashamed of; it is a pillar of human culture that we should take pride in.

In my studies, I explored two anthropological theorists in depth—Christopher Knight and Annette Weiner—who, in different ways, proposed that menstruation was the basis of human culture. This disruptive idea runs counter to prevalent cultural origins theories, which—with little evidence— mostly take for granted that men were the (violent) prehistoric agents of human development. Moreover, Knight contends that any cultural origins theory should comport with the time-tested theory of evolution. Instead, he says, most origins theories simply project the hierarchical social structure of the present (i.e., patriarchy/patriliny) onto the prehistoric past, without proposing any evolution-friendly triggers of the primate-to-human shift. At the heart of this critique is the insight that, for culture to have emerged during the Paleolithic period (which lasted from 2.6 million years ago until 12,000 years ago) and persisted for millennia, early hominids had to have found a way out of the animal state that entails perpetual battle over food and sex. That is, without having established a relatively peaceful and egalitarian social structure—as seen in present-day hunter-gatherer groups—humans could not have developed a system of shared meaning (culture) and passed it on to succeeding generations. Both Knight and Weiner posit an original matrilineal social structure as the likely (peaceful) crucible of the “creative explosion,” the burst of symbolic culture in Africa around 90,000 years ago that has persisted to this day.

In Blood Relations: Menstruation and the Origins of Culture, Knight proposes that hominid females, after having moved from the expansive but drought-stricken central savanna to the cramped riverine East African Rift, where they had to live in closer quarters than ever, began menstruating and ovulating in synchrony. He argues that they ultimately leveraged this menstrual/ovulatory synchrony to undermine alpha males’ sexual monopoly of them (in what would have been the existing primate social system), in order to get provisioning help for their young from less dominant males. This led to a relatively egalitarian distribution of food and sex, which in turn established the peace required to perpetuate (matrilineal) culture through the generations until the Bronze Age (about 8,000 years ago).

In the primate social system on the savanna, alpha males would have sexually monopolized any asynchronously ovulating females; but, Knight argues, after moving east, these early women broke that monopoly by taking advantage of the “un-policeability” of their mass ovulation and by imputing cosmic significance to their collective monthly bleeding. That is, by “magicalizing” the apparently moon-governed cycle and by standing in ritualized solidarity, first as sexually unavailable and secluded during the menstrual half, and then as sexually available to the less dominant males during the ovulatory half—in exchange for meat hunted during the menstrual seclusion— women in effect forged the first standing contract.

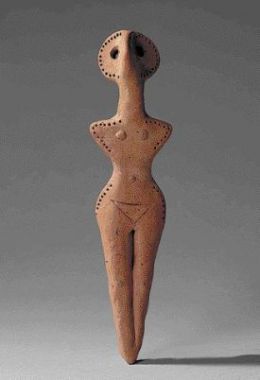

Since women’s reproductive imperative would have been to get provisioning help for their young, who, with their large crania, had to be born in a much more helpless state than the young of any other species, this social innovation would have been adaptive in evolutionary terms. What’s more, the fairly equal distribution of food and sex occasioned by the contract would have established the peace needed to share meaning and then pass it on to successive generations—that is, it established the ground for sustained culture. Seen in this light, the nearly universal modern stigma on menstruation begins to look like a very deliberate and comprehensive reversal of what appears to have been a nearly universal reverence for it. Indeed, the feminine images and themes of the earliest art and literature seem to show respect for menstruation. And, since menstrual seclusion rituals appear to have involved “disguising” women as the wrong species for sex, it is not surprising that in much prehistoric art, women and goddesses were figured as animal-human hybrids, particularly as bird-women. The delicate forms and vulnerable expressions of many of these prehistoric figurines seem to indicate that it was particularly important to honor girls menstruating for the first time.

Weiner’s main work, Inalienable Possessions: The Paradox of Keeping-while-Giving, challenges the anthropological chestnut that men initiated culture when they began exchanging women as gifts. In her study of traditional Oceanic cultures, she too found evidence of archaic female solidarity and, like Knight, saw it as rooted in an original matrilineal system. According to Knight, for women and men alike, prehistoric social identity would have come from one’s mother group, such that women’s brothers, uncles, and nephews would have been their allies and protectors, even as they brought the meat they hunted to their wives in other mother groups. Looking at patrilineal societies in Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia, Weiner saw vestiges of this matrilineality in their current marriage and exchange traditions.

She noticed that, even though women move in with their husbands upon marriage, they create reciprocal obligations back to their mother groups by weaving highly prized textiles for their in-laws. Thus, she says, women act as agents of their mother groups (in which they are particularly cherished by their brothers). She also noted that the high exchange value of woman-produced textiles is rooted in the belief that women’s menstruation makes their cloth sacred and capable of conferring what Weiner calls “cosmological authenticity” on family lineages. In some of these societies, women have for ages produced supremely valued feather cloaks that have signaled power, status, and identity; and, among the Maori, the patron deity of women’s feather cloak weaving is a bird-woman hybrid.

After seeing a bird lady appear again and again in my studies—in ancient, medieval, and modern sources alike—mainly as some version of a fairy tale type called the swan maiden, I was struck by the tale’s ubiquity (nearly every culture on Earth has a swan maiden story) and by its longevity (think poems of the Sumerian goddess Inanna from the 4th century B.C.E., ancient myths of the Greek Aphrodite, Vedic verses about the dawn goddess Ushas, the medieval French legend of the Melusine, Irish selkie legends, the modern Swan Lake ballet, the even more modern films Splash or Desperately Seeking Susan, or the contemporary lore surrounding the African Mami Wata). In my chapter in Menstruation: A Cultural History, I argue that, in spite of its many versions and retellings, the swan maiden tale—a story of female longing for and return to a lost otherworld—is essentially a primordial archive of the lost matrilineal system posited by Knight and Weiner.

The swan maiden makes an appearance in Lizzy in the old woman’s recounting of the story of the Descent of Inanna, the oldest written poem ever found. While she doesn’t give Lizzy the evidence I found that connects Inanna to prehistoric menstrual rituals (e.g., temple staff “tracking” her period, or the etymological link between her name and the Sumerian word for menstrual cloth), she does make Inanna’s world-renewing underworld descent/ascent a metaphor for the menstrual cycle, likening the descent (the cycle’s menstrual side) to a contemplative retreat during which a girl can weigh what in her world needs renewal. Within this metaphor is the deeper suggestion that, since menstruation enabled human thought and reflection on repeating bodily and heavenly patterns—effectively awakening humans from their primate “sleep”—it still offers women the opportunity to reflect on the patterns in their lives that need renewal. The power to make the world new again? What could possibly merit more pride?

Jacqueline Thomas earned her PhD in English literature at The University of Texas at Austin in 2007. Menstruation: A Cultural History is published by Palgrave Macmillan and available in a number of university libraries. Lizzy & the Light Below is available through Amazon/Kindle.