Sometimes, when it seems that progress toward the elimination of harmful menstrual stereotypes, myths, and misinformation is slow or even stalled, it is bracing to take a look back at the kinds of educational materials, marriage manuals, and sources of advice that women were offered in the past in order to be reminded that progress does actually exist. Consider, for instance, an effort to enlighten women about sex, marriage, and the menstrual cycle from the early 20th Century.

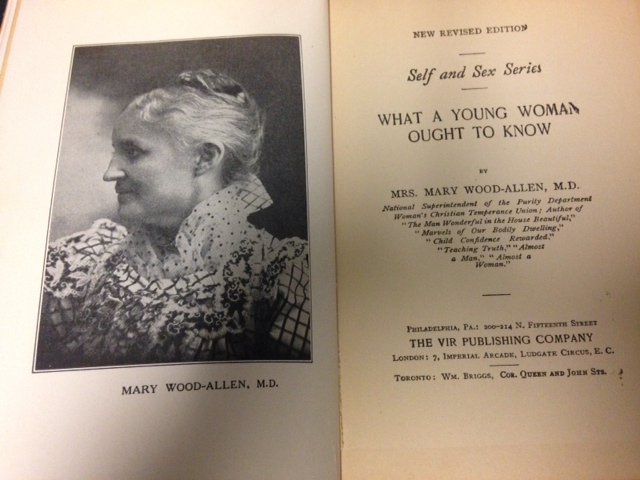

One hundred years ago, in 1913, a book appeared in the “Self and Sex Series” titled, What a Young Woman Ought to Know by an author identified as Mrs. Mary Wood-Allen, MD. Her credentials, displayed on the title page, include the following: “National Superintendent of the Purity Department Woman’s Christian Temperance Union,” and she is credited with having written six other books, including Almost a Man and Almost a Woman.

To get a hint of the direction the book takes in its effort to instruct young women in what they ought to know a glance at some of the chapter titles may suffice:

Ch. V – “Breathing”

Ch. VI – “Hindrances to Breathing”

Ch. VII – “Added Injuries from Tight Clothing”

Ch. XVI – “Some Causes of Painful Menstruation”

Ch. XVII – “Care During Menstruation”

Ch. XIX – “Solitary Vice”

Ch. XXVII – “”The Law of Heredity”

Ch. XXXIV – “Effects of Immorality on the Race”

Ch. XXX – “The Gospel of Heredity”

As these titles suggest, the book manages to link menstrual education with some of the most virulent eugenic nonsense that had gained widespread acceptance in American science and politics of the time, the same sham-science that led to sterilization of disabled people and African-Americans in the U.S. and found a welcome home in Nazi Germany in the following decades.

Perhaps the best way to communicate the stupidity of the book’s content is to allow it to speak for itself. Consider the explanations of menstrual discomfort and the effects of bad reading habits:

“Whenever there is actual pain at any stage of the monthly period, it is because something is wrong, either in the dress, or the diet, or the personal and social habits of the individual.” (119)

“Romance-reading by young girls will, by this excitement of the bodily organs, tend to create their premature development, and the child becomes physically a woman months, or even years, before she should.” (124)

“…if girls from earliest childhood were dressed loosely, with no clothing suspended on the hips, if their muscles were well developed through judicious exercise, they would seldom find it necessary to be semi-invalids at any time.” (146)

The underlying disdain or fear of sexual pleasure is expressed in the chapter about masturbation, titled “Solitary Vice,” in which it states, “the reading of sensational love stories is most detrimental…This stimulation sometimes leads to the formation of an evil habit, known as self-abuse….The results of self-abuse are most disastrous. It destroys mental power and memory, it blotches the complexion, dulls the eye, takes away the strength, and may even cause insanity.”

As if these dire consequences were not bad enough, it turns out that once one has inflicted these conditions on one’s self, they can enter the girl’s genetic code and be passed along to future generations. Even a girl’s clothing choices can have long term, disastrous effects: “The dress of women is not merely an unimportant matter, to be made the subject of sneers or jests. Fashions often create deformities, and are therefore worthy of most philosophical consideration, especially when we know that the effects of these deformities may be transmitted.” (223)

The author minces no words as to the effects on the children of such a careless mother: “The tightly-compressed waist of the girl displaces her internal organs, weakens her digestion, and deprives her children of their rightful inheritance. They are born with lessened vitality, with diminished nerve power, and are less likely to live, or, living, are more liable not only to grow up physically weak, but also lacking in mental and moral stamina.”

The book goes on like this at length, eventually pointing out the debilitating effects of alcohol and tobacco consumption upon both the user and future generations due to the impact on the genetic material. This is not surprising since, after all, the author is an officer in the Women’s Christian Temperance Union: “[Women] ought to understand the effect of alcohol and other poisons in producing nerve degeneration in the individual, and its probability in his posterity.” (224)

The unabashed nature of the racism in these discussions is striking. Women are importuned to meet their responsibility to see to maintaining their race’s superiority: “There is another influence at work in causing race degeneracy concerning which the majority of girls are ignorant, and that is immorality.” Here, women are charged with the responsibility to live an upright life, not only for the immediate benefits to their society but due to their role as protectors and progenitors of their race’s survival.

In effect, the entire design behind the book’s surface effort to “educate” young women about sexuality, health, and reproduction is the promotion of notions of racial superiority and the importance of protecting the group’s “Gospel of Heredity.”

There are many more such statements in What a Young Woman Ought to Know that might elicit a gasp, a smile, or a sad (and superior) shake of the head. But perhaps we should also recognize that though many of its ideas strike us as quaint, benighted or vicious, we cannot let down our guard against those wrong or destructive notions that are still in circulation, some of which we might even subscribe to ourselves.

Next time: a look at a 1926 marriage manual.