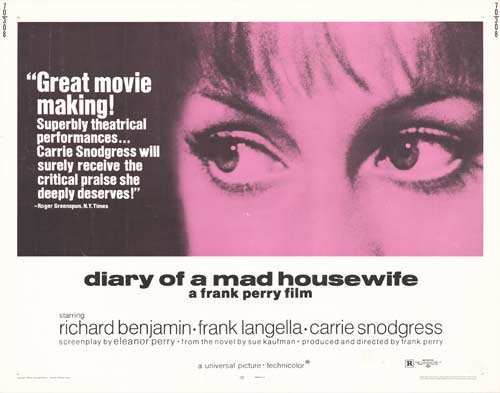

In 1967 a new novel, Diary of a Mad Housewife by Sue Kaufman, struck a chord with Boomer Generation women, the post-war era’s cohort who were already the subject of Betty Friedan’s 1963 The Feminine Mystique and who are characterized today in TV’s Mad Men. The novel became a best seller and shortly received a successful film treatment in 1970 with a script by Eleanor Perry and directed by her husband Frank Perry. Carrie Snodgress was nominated for an Oscar for her performance in the title role, and Richard Benjamin, as her obnoxious husband, also received rave reviews. The novel is still in print having been reissued in 2005 with an introduction by Maggie Estep who was only four years old when the novel was first published.

In 1967 a new novel, Diary of a Mad Housewife by Sue Kaufman, struck a chord with Boomer Generation women, the post-war era’s cohort who were already the subject of Betty Friedan’s 1963 The Feminine Mystique and who are characterized today in TV’s Mad Men. The novel became a best seller and shortly received a successful film treatment in 1970 with a script by Eleanor Perry and directed by her husband Frank Perry. Carrie Snodgress was nominated for an Oscar for her performance in the title role, and Richard Benjamin, as her obnoxious husband, also received rave reviews. The novel is still in print having been reissued in 2005 with an introduction by Maggie Estep who was only four years old when the novel was first published.

There is a time travel quality to reading the novel today, or perhaps it’s like visiting some remote, foreign culture. So much of it is dated to the point of obscurity: pop culture references are lost; jargon and slang are quaint; fashions are out; brand names no longer exist. Most striking of all are the iron-clad gender rules the characters live by. The Husband, Jonathan, is a condescending, arrogant, inconsiderate bore. The Wife, Teena, is a shrinking, obedient, victimized mouse who timidly scurries about until a hot sexual affair with another self-centered cad and the collapse of her husband’s job and ambitions finally suggest, at the novel’s end, that maybe there’s hope to be found in the ruins of their miserable lives. Today’s readers are unlikely to feel much sympathy for her passive acceptance of her plight.

In the midst of this otherwise overwrought and curious artifact from a pre-Second Wave, pre-consciousness, pre-Steinem, pre-SMCR age, there can be found several glimpses into the menstrual values of the times. Through the lens of literary products such as this we can sometimes gain perspectives on both past and present. In this way Diary of a Mad Housewife enters the literary menstrual canon.

Considering the way any mention of menstruation was assiduously avoided at the time, the period references are surprisingly frank. And of more significance, the story avoids any cheap, clichéd attempts to connect Tina’s “madness” with any sort of hormonal fluctuation.

Within the first ten pages, having identified the fact that she’s feeling unhinged, paranoid, and depressed, Teena speculates that perhaps she’s suffering from “a Pre-Menopausal Agitation,” brought on by having recently turned thirty-six, the same age as Marilyn Monroe when she presumably committed suicide – “Thirty-sixitis.” Her husband is urging her to pay a visit to her old psychiatrist, the peculiarly named “Dr. Popkin.”

The rest of the narrative, in the form of a secret diary that she is keeping, details Teena’s trials and tribulations with her children, party caterers, friends, house keepers, lover, husband, and assorted others, including a social acquaintance who ducks a dinner engagement with a crafty menstrual evasion (“I seem to have these perfectly beastly curse cramps.”) that turns out to have been a lie.

Teena’s menstrual values are also detailed in a description of difficulties scheduling trysts with her obnoxious lover, George. At one point, juggling party chores, parenting, domestic duties, hairdresser and dental appointments, she tells him, “I can see you early in the week. It has to be early because I’m due to get the curse about the middle of the week.” George responds, “I don’t mind that,” and Teena answers, “I do.”

The “no menstrual sex” rule reflects the menstrual ethos of the times as well as serving as a means of illustrating the limits of the character’s freedom from sexual inhibitions despite the lustiness of her sexual performances with George – and they are “performances,” for her acts of defiance and at least a momentary flaunting of convention.

Eventually, the story moves toward climax with an ancient, reliable plot device: a late period. Once again relying on the derogatory slang expression, Teena writes in her diary, “the curse is now five days overdue.”

The next entry in the diary begins, “Twelve days late the curse is, counting today. I’ve been so frantic I can’t even write it here.” What follows reveals the character’s (or the author’s?) desperate view of the marital situation. For nearly 300 pages we have witnessed a miserable woman in a miserable marriage to an execrable man. Yet, suddenly faced with the possibility that her late period means that her infidelity will be revealed and her husband will divorce her she has an epiphany, “I’ve finally begun to perceive that the life I’ve been living is right for me, that I’m in the right niche. That if I divorce Jonathan or Jonathan divorces me, I’ll never find the right niche again.”

In desperation she goes to see George, hoping for both sympathy and money to get an abortion. He gives her neither. Instead, in response to her slap he belts her in the face, laughs at her hysteria and calls her “Madame Ovary.”

The plot begins to wrap up in a tidy bundle. Teena gets her period with a case of “really terrible cramps,” her husband confesses to an affair and that he has lost their savings and his job is threatened. As he recites a litany of his failures, “[she] sat shivering and staring at the floor. The kitchen was warm, but I was freezing. Also, my cramps were back, and unbelievably bad.” The novel ends on a note of reconciliation yet the cramps remain. The menstrual metaphor lives on.

(Next post we’ll take a look at another novel published the same year with remarkably similar themes, characters, and an underlying menstrual plot line: Rosemary’s Baby.)

Wouldn’t a late and abnormally painful period also be evocative of a miscarriage?

Yes, bethpresswood, good point, though that possibility is not identified in the book. But you might be interested in the way menstrual-related pain is treated in Rosemary’s Baby which will be discussed in next week’s post.