Recently menstrual shame made the front page of the New York Times in paragraph one of an article titled, “For Women in Street Stops, Deeper Humiliation.” The piece reported on an ongoing debate about the “stop and frisk” policies of the police who, seemingly at random, stop individuals in public places and pat them down or require them to empty their pockets and purses if the police have reason to suspect they are in possession of drugs, guns, or other illegal materials. The opening sentence of the article by Wendy Ruderman presents a dramatic scene:

Shari Archibald’s black handbag sat at her feet on the sidewalk in front of her Bronx home on a recent summer night. The two male officers crouched over her leather bag and rooted around inside, elbow-deep. One officer fished out a tampon and then a sanitary napkin, crinkling the waxy orange wrapper between his fingers in search of drugs.

The language is rife with invasive images: “crouched over,” “rooted around inside, elbow-deep,” “fished out a tampon,” “crinkled the … wrapper between his fingers.” It goes on to also have the officer handling her birth control package, further humiliating her.

Just a month later, again in the New York Times, this time a piece by their regular advertising columnist, Stuart Elliott, the following appeared: “In a Forthright Campaign, More Unmentionables Mentioned.” Is anyone going to be surprised to learn what unmentionable was mentioned? Though the main topic was the new approach to advertising the laxative Senokot, Elliott links it to earlier restrictions against advertising menstrual products:

“Ads for products like laxatives, toilet paper, condoms and tampons have become more forthcoming as societal attitudes on what can be discussed in public . . . have significantly changes. Consumers of a certain age can still recall ads for Modess sanitary napkins that uttered only two words, ‘Modess … because,’ well, because menstruation was deemed a taboo topic.”

There’s nothing new about this phenomenon nor about the titillating fascination with the taboo itself. A few years ago (March 2008, p. 281) Glamour magazine ran a piece called, “Tampon mortification!” about the shame of dropping a tampon in public. But this time they turned it into a prank by staging the accident and photographing the responses. As the tag line put it, “We’ve all had a stray one fly out of our bag. But a boxful? Volunteer Sabrina Fernandez lives the nightmare.”

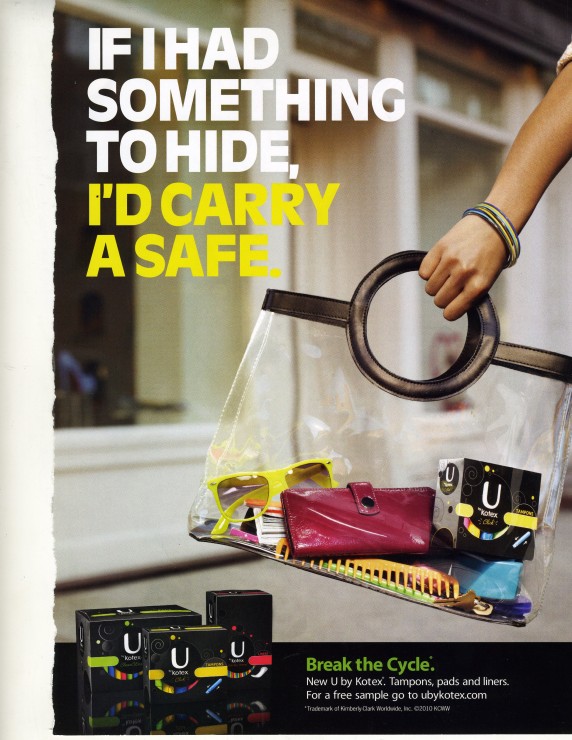

The most noteworthy advertising campaign to confront the taboo in recent years has been the assertive and cleverly named U by Kotex series. Comprised of little more than new packaging (black boxes containing neon colored applicators and envelopes for pads) and yet another punning slogan, “Break the Cycle,” the campaign urges women to flaunt their periods without shame.

Yet it is both weird and worrisome that the woman whose bag and arm we see in the ad apparently finds it necessary to carry an entire box full of the product with her rather than the usual few. Should we be concerned? Is she experiencing menorrhagia or, to the contrary, is this an expression of menstrual activism?