Laura Eldridge’s new book In Our Control: The Complete Guide to Contraceptive Choices for Women (Seven Stories Press, 2010) isn’t kidding with that subtitle. The last time I remember reading so much detail about contraceptive options was poring over Our Bodies, Ourselves when I was in my 20s.

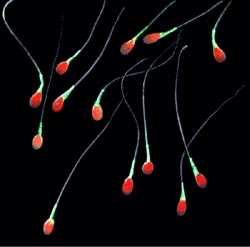

Eldridge reviews every method of birth control known to modern woman–and, importantly, some that aren’t widely known. She even briefly reviews the history of contraception in 19th and 20th centuries, reminding us that birth control is not a new invention. People, especially female-bodied people, have struggled to control their fertility from pretty much the first moment humans figured out how it worked.

In Our Control differs from Our Bodies, Ourselves in offering more than just the mechanics of both hormonal and barrier methods: Eldridge provides a history of each method and analysis of the political and cultural contexts of their use in the 21st century U.S.

For example, the chapter about the morning-after pill (also known by either the brand name Plan B or as emergency contraception, EC) discusses the political battle to achieve Federal Drug Administration approval, including Susan Wood’s resignation from the FDA’s Office of Women’s Health over what she believed to be “willful disregard of scientific evidence showing Plan B to be safe.”

Eldridge extensively addresses the relationship between birth control and menstruation, focusing one chapter specifically on the use of hormonal contraception to reduce or eliminate menstrual cycles. She draws upon a wide range of resources to illustrate the cultural attitudes and contexts of menstruation, from stories of the role of birth-control pill co-developer John Rock’s Catholicism in the three-weeks-on/one-week-off dosing of the first pill to a Saturday Night Live parody of advertising schemes for menstrual suppression drugs (with Annuale, you’ll menstruate only once a year, but hold on to your fucking hat!).

The book also covers environmental impacts of contraception, the politics of HPV vaccinations, ongoing research into a birth control pill for men and natural methods of birth control such as fertility awareness–which Eldridge carefully distinguishes from the much-maligned “rhythm method.” She notes that the method approved by the Catholic church is properly called a calendar-based method and involves estimating when ovulation occurs and avoiding sex during that time. Fertility awareness, however, involves a more complex, systematic attention to physiological markers of female fertility. It requires careful monitoring of waking temperature, vaginal sensation, position of cervix and cervical fluid, as well as dates of menstrual flow and sexual activity. Eldridge cautions that fertility awareness is too complicated to be taught in a short chapter, and that observing and charting one’s cycle must be done “for a significant amount of time before you begin to rely on it for contraception.”

Laura Eldridge learned women’s health writing at the side of the late women’s health advocate and activist Barbara Seaman, and it shows. She contextualizes her work with her own experience and preferences, but provides thorough documentation so that women can more easily make their own decisions. This is women’s health activism at its best. Feminism isn’t just about choices, but about having access to information and resources to make informed, authentic choices–and that is only possible when reliable and comprehensive information is widely available.

Cross-posted at Ms. magazine blog.

https://www.cleveland.com/healthfit/index.ssf/2009/11/cwru_museum_chronicles_long_hi.html

Hope the above link works. This blog reminded me of my visit to the above museum of birth control at Case Western University Campus. Anyone living in or around the Cleveland area should visit. While it is a small museum the items in it are fascinating. To be sure women have been using birth control for a very long, long time. BTW, I didn’t completely read the article, I’m on the run, but it gives the details on the museum.