Down the Washington Mall from the popular National Air and Space Museum and the National Gallery of Art lies the sprawling National Museum of American History with its fascinating collections of the history of American material culture: early plows, bicycles, mail boxes, tobacco tins, thimbles, shoes, harnesses, tools, stoves, and every other imaginable artifact from every aspect of American life. The collection spans domestic, economic, military, technological, media, educational, and virtually every other realm of human endeavor.

And, locked away in a climate-controlled room next to cabinets full of objects associated with medical, disability, reproductive and health concerns are drawers full of items that woman have used to manage their periods.

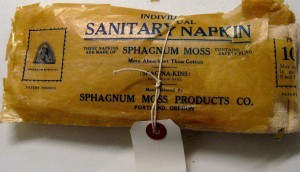

I was given a private tour of the collection by Dr. Katherine Ott, a curator of Science, Medicine, and Society at this branch of the Smithsonian and lead editor of Artificial Parts, Practical Lives: Modern Histories of Prosthetics. Her knowledge of the collection, its content, sources, and significance was coupled with a generous enthusiasm in sharing it. The item we both marveled at most was a package of sanitary napkins made of sphagnum moss. Sphagnum moss is a substance commonly used today to line hanging pots of ferns and other plants to absorb and hold excess moisture. It was also used by native American mothers who stuffed the moss into papoose back packs — early environmentally friendly disposable diapers. This menstrual management device consisted of a strip of moss wrapped in gauze and provided with safety pins to attach it inside an undergarment.

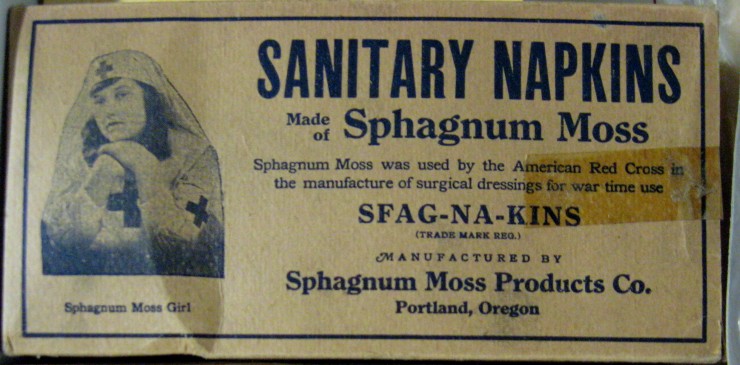

The packaging itself contained several details that revealed much about the menstrual ecology of the times. The demure picture of the “Sphagnum Moss Girl” dressed in a uniform echoing Clara Barton’s Red Cross nurses was coupled with a line that reinforced the picture, “Sphagnum Moss was used by the American Red Cross in the manufacture of surgical dressings for war time use”. This is strikingly similar to the descriptions used in the earliest advertisements for Kotex, which the company claimed was originally produced for use in front-line hospitals during World War I (or “the World War”, as it was described at the time before a second came along).

And, in true ad-speak fashion, the product was given a catchy name: “SFAG-NA-KINS”. The package included a folded page titled, “A Short History About Sphagnum Moss From Which Sfag-na-kins Are Made”. The pamphlet includes details about how the substance was used by the Japanese army during their war with Russia and how it was perfected by various doctors and medical researchers, including one Dr. J.B. Porter of McGill University. Apparently competition from wood pulp-based products such as Kotex was already starting to take shape, as the pamphlet goes on to claim, “The SFAG-NA-KINS will be found to be greatly superior to anything else now on the market, and one of them should be equvilent to three or more of the Cotton Sanitary Napkins. The complete elimination of any stain to garments is only one of the many superior features of the SFAG-NA-KINS”. The fact that pulp products won out in the market may be due to the fact that “Kotex”, with its resonance to “cotton”, a substance more familiar and acceptable than moss, is a catchier name than the hard-to-pronounce and “sfag-na-kins,” not to mention the unsavory image of walking around with a wad of moss between one’s legs.

In addition to this rare mass marketed moss product, the collection contains every imaginable brand of pad, tampon, cup, and belt as well as drawers full of cycle management drug products including one of the original circular birth control pill dispensers. Adjacent cabinets were filled with hundreds of condom packages, pessaries, IUD’s, cervical caps, devices for containing a prolapsed uterus, and related marketing and educational posters, flyers, and brochures.

My tour of the Smithsonian collection and Dr. Ott’s insightful narration of its history enhanced my understanding of the complex connection between the biological characristics of the menstrual cycle and the social and economic context in which it exists.

Thanks David for a good read! Is the collection open to anyone?

Hi Josefin,

Glad you found it interesting. The archive is not open to the public on a walk in basis but if you have a particular research project in mind and want to see the holdings, contact the curator whose name I mentioned and she’ll probably make arrangements for you to visit.

My blog post only scratched the surface on the fascinating items there

Jealous me! Such a treasure trove! Glad you got a look, David.