Birth control in the U.S. has become synonymous with drugs and devices. The pill, patch, or ring; Depo-Provera or hormonal implant; copper IUD or Mirena IUD; traditional hormonal birth control or long-acting reversible contraceptives. All impact the function of the menstrual cycle; some suppress it completely. As a pro-choice menstrual cycle advocate I take issue with the fact that keeping your cycle and contracepting effectively are now considered mutually exclusive.

A widely published Associated Press story tells us that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists now recommends hormonal implants and IUDs as the best birth control methods for teenagers. The research this recommendation is based on did not even study pregnancy outcomes for women using condoms, barriers, or fertility awareness methods. These methods were not among the free contraceptives offered to study participants. Another story reported that “the new guidelines say that physicians should talk about (implants and IUDs) with sexually active teens at every doctor visit.” This sounds like a hardcore sales pitch to me. I expressed my concerns about pushing LARCs on teenagers in a previous re:Cycling post.

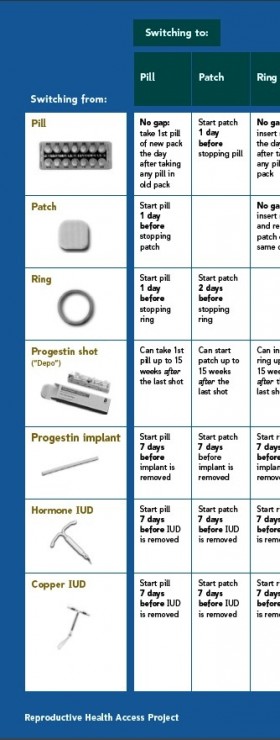

Drugs and devices also figure prominently in Switching Contraceptives Effectively. New York Times health writer Jane E. Brody writes about the mistakes women make when switching between birth control methods that can result in unintended pregnancies. The reasons women switch are explored and a link to a resource on how to switch methods successfully is provided.

Drugs and devices also figure prominently in Switching Contraceptives Effectively. New York Times health writer Jane E. Brody writes about the mistakes women make when switching between birth control methods that can result in unintended pregnancies. The reasons women switch are explored and a link to a resource on how to switch methods successfully is provided.

The Reproductive Health Access Project developed the pamphlet to help women prevent gaps in contraception when they change methods. The premise is a good one:

What’s the best way to switch from one birth control method to another? To lower the chance of getting pregnant, avoid a gap between methods. Go straight from one method to the next, with no gaps between methods.

But the pamphlet developers made the huge false assumption that all women just need or want to try another drug or devise. It focuses ONLY on these method — how to switch from the pill to Depe-Provera or the copper IUD, or how to switch from the Mirena IUD to the progestin implant. Condoms and barrier methods are considered useful ONLY for the transition period between drugs and devices. Fertility Awareness Methods are ignored completely. The resource comes across as propaganda for drug- and device-based birth control methods.

Neither Brody nor those behind the Reproductive Health Access Project seem to understand that this approach contributes to the unplanned pregnancy rate by failing to acknowledge that many women are fed up with contraceptive drugs and devices. These women want support and information to switch away from these methods. They are falling though the contraceptive gap created by this failure.

Is it any wonder that some women stop using their contraceptives without talking to their physicians? Maybe they are fed up with doctors like Ruth Lesnewski, education director of the Reproductive Health Access Project, who offers trite admonishment that side effects “will go away with time” and insists that caution about using long-acting methods like the IUD or hormonal implant is “outdated.” Real health issues are associated with all these methods. I guess Dr. Lesnewski doesn’t read health blogs where women document their frustration about side effects and dismissive health-care providers.

This article places blame for contraceptive failure on women not knowing how birth control works, instead of where the blame really belongs — on the blind spot that keeps sexual and reproductive health-care providers from seeing, and serving, women who are sick and tired of drugs and devices.

As for the ACOG recommendation on the best birth control methods for teens? It’s just a step away from coercive, patriarchal decision-making by doctors for teenage girls, and a threat to the sexual agency of many young women.

I find it interesting that long-acting methods were primarily developed for women in developing countries who were undoubtedly coerced into using them, and now they are being introduced in developed countries to the young and the poor. For middle class women the sell is “convenience” but the lines are blurring. Yes, there’s a difference between Chinese women being forced to have an IUD and to keep it no matter what and suggesting to teens at every doctor visit that they try a LARC. There’s a difference between injecting women in Africa with Depo Provera with no information and pushing these methods on teens too. But teens are coerced into so much already by schools, parents, friends, culture and this argument is being framed as if you don’t use a LARC you and your parents are irresponsible (and not modern, up to date and trendy). And as always, the suggestion is more and more so if you DO get pregnant you are very much on your own. Things are already this way here in the US but if a teen doesn’t have a LARC and gets pregnant in a school full of teens on LARCs – well, the community and society can wash its hands of her with what will be seen as just cause. I recall a Slate article referred to those not wanting to use the pill as “pill refuges” – what will happen to those that chose not to use LARCs? You can almost sense that they HOPE they will get pregnant – the ultimate justification of mass application of these devices.

What evidence do you have that teenagers were “coerced”? The project is called Contraceptive CHOICE. What’s wrong with choosing a method that is convenient, or that your parents won’t discover in your backpack?

I spend a lot of time in clinic seeing women with a history of unintended pregnancy. I also see a lot of women who have no interest in a pregnancy soon. It’s the rankest paternalism to suggest that women are incapable of understanding the risks of contraception (which, incidentally, are much lower than the risks associated with pregnancy) and choosing its use. Why would you decide for another woman that the high failure rates of FAM and barrier methods (and I am talking actual failure rates, not theoretical, since I do live in the real world) are preferable? Why is it your place to tell a woman who does not feel she can ask her partner to use condoms that she should be using a barrier method, or periodic abstinence?

Welcome to the real world. I practice here. I give my patients all their contraceptive options and risks. I don’t really care what method they choose, as long as they like it well enough to use. Your misplaced concern speaks volumes about the lack of confidence you have in the ability of women to make their own choices.

Thanks for your comments Meghan. I, too worked in the real world as a sexual health educator. I heard more stories than I can count from young women who were fed up with their inability to find information, support and services to use non-hormonal methods. The point I am trying to make is that many women don’t want to use drug- and device-based birth control. Many of their concerns about side effects are actively dismissed or ignored. This is paternalism. As is doctors telling young teenagers that implants and IUDs are the best methods for them. On what basis besides effectiveness? Is that all that matters?

My other point, is that if choice means comprehensive choice, then why are there not better programs and support systems in place to serve women who want to learn to use non-hormonal methods effectively and confidently?

I’ve been a member of the mainstream pro-choice sexual and reproductive health community for over 25 years. I am pointing out a deficit in service delivery that has remained constant for too long. Where do women who don’t want to use hormonal methods go for information, services and support to actually access these alternative methods? Perhaps your clinic does a better job than most in offering diaphragm fittings or skilled instruction in Fertility Awareness Methods. I’m not deciding for women that they should use these methods, I’m asserting that they should have better access to them if they want to use them. And for the most part they don’t, or they are dissuaded from using them on the false assumption that these methods are totally unreliable. As you said, “as long as they like it enough to use.”

I don’t think my concern is misplaced. My work experience has taught me that many women are not getting the contraceptive assistance they are seeking. You think I lack confidence in the ability of women to make their own choices. I think most sexual and reproductive health-care providers lack confidence in the ability of women to use non-hormonal methods successfully. Now, with the ACOG recommendation, it seems they even lack confidence in women using the pill, patch, and ring successfully. That speaks volumes.

I find it terribly sad to think that the parameters for choosing a birth control method have come down to convenience and ability to hide it from one’s parents, rather than what best serves a teenager’s sexual and general health and well-being.

I didn’t say that teenagers were coerced in the Contraceptive Choice Project to chose LARCs. The participants were college students. Who knows how the methods were presented to them. I do contend that with the ACOG recommendation, doctors will be urging teenagers to choose IUDs and implants. Coercion is a real possibility.And how difficult might it be for them to advocate on their own behalf for removal if they don’t like them?

I, too, worry that the pressure to use these effective but invasive methods (so problematic for many womenm) will only increase. One can foresee a time when it will be completely unacceptable to have an unintended pregnancy, the argument being that all women should be using LARCs. And those who won’t will be “uncompliant” and “irresponsible.”

Half of all pregnancies in the US are unintended. The patients I see have tried the pill, the patch, the ring, condoms, Depo. They are the first to tell you that they do not use them consistently. There’s a body of research in nursing showing that medication, even for life-threatening conditions like diabetes and heart disease, are not taken consistently. Many of my patients work two jobs, or have child care issues, or no transportation to pick up their refills.

It’s not as if the choice is between two equally-effective modes of contraception. The failure rate on LARCs is much lower than the actual failure rate of CHCs. Pregnancy itself carries more risk than any form of birth control, and therefore failure rates must also be considered a risk.

It’s important too to remember that for many OBs, trained in an earlier time, limit IUDs to married women who have had at least one child, despite the lack of research supporting this limit. For ACOG to take this stand is a huge step forward for women to be able to access all forms of contraception, including the often underused IUD.

I counsel teenage girls about birth control daily. Respectfully, I haven’t met one yet that I would bet on to successfully avoid pregnancy with condoms and fertility awareness alone. Teenagers and 20somethings are KIDS. They can’t be expected to manage their lives like adult women. As it is, I see about 1 in 50 back again later in the year to refer her for an abortion because she couldn’t remember to take the pill, pick up that next pack of patches or come back on time for the shot. I *do* steer young women to injections and implantables. It isn’t a conspiracy, it’s reality. Don’t mistake this for patronization. I take my obligation to them seriously. If they come to me asking me to help them not get pregnant, I am going to do my VERY BEST to help them not get pregnant. Condoms and fertility awareness are not anywhere approaching the very best I have to offer them, so I don’t even go there.

Hi Megan,

I can only speak from personal experience as a woman who was coerced into talking the pill with no information given to me. Actually my family doctor prescribed the pill without telling me anything about the side effects. I am not dumb, but I did make a mistake in that I listened to my doctor. Almost all of the women I know listen to their doctor, we lead busy lives and do not have time to do our own research. I find your comments upsetting because you fail to acknowledge STI’s. I believe that if I counseled young girls my number one priority would be encouraging them to use condoms to protect themselves against STI’s and pregnancy. I know from being a teenager myself with lots of teenage friends that once girls are on hormonal contraception or device based contraception they no longer use condoms because they think they are safe. Sadly, they are not safe from STI’s. I think that condoms are extremely effective when used properly and that the morning after pill is a good back up if something goes wrong. All I ever hear is women complain about hormonal birth control. Once again I can only talk from personal experience.

I’ll comment on four of your statements.

1. “The patients I see have tried the pill, the patch, the ring, condoms, Depo. They are the first to tell you that they do not use them consistently.”

It’s time we get to the root of why women use these methods inconsistently. This requires that we take seriously women’s concerns about how such contraceptives make them feel, and stop dismissing side effects as a nuisance they must accept and get used to. This is “pat her on the head and tell her they’ll go away” paternalism.

It also requires that we teach women how their menstrual cycles work before we teach them about hormonal birth control and how it works to prevent pregnancy. Don’t tell me women know this; my experience is that they don’t.

2. “The failure rate on LARCs is much lower than the actual failure rate of CHCs.”

The failure rate for LARCs is lower because these methods are much harder for women to stop using on their own. They have to see the doctor to have them removed if they don’t like the side effects. No wonder ACOG is recommending them for teens. More control means greater effectiveness. This has both positive and negative implications.

3. “It’s not as if the choice is between two equally-effective modes of contraception.”

I didn’t say it was. My argument is not about effectiveness. I’m saying the choice between more invasive methods like IUDs & implants and non-invasive methods like barriers and FAM is the woman’s choice to make. If she chooses to reject hormonal methods, IUDs or implants, then it is her right to do so, and she should be able to count on support from her sexual and reproductive health-care provider to make this choice.

I am arguing that women who want to learn to use barriers and FAM effectively and confidently have few places to go for information and support. Your position suggests that your clinic does not provide this support, that you do not see this as your responsibility as a sexual and reproductive health-care provider. This is your decision to make. I don’t agree.

4. “For ACOG to take this stand is a huge step forward for women to be able to access all forms of contraception, including the often underused IUD.”

Your final statement seems to prove my point that “all forms of contraception” in your realm of practice includes ONLY drug- and devise-based methods.

Contraceptive choice means not only having the choice to use any of the broad range of available hormonal contraceptive methods, but also having the choice NOT to use them. Is it the clinician’s or doctor’s place to dissuade women from rejecting hormonal methods? Is it their place to refuse to offer barriers and FAM as valid choices? Based on what? Unexamined bias against non-hormonal methods? Belief that women just aren’t capable of using them effectively? Assumption that you know what’s best for teens and women?

As I said at the beginning of my post, the prevailing opinion in the sexual and reproductive health community that you represent is that maintaining ovulatory menstrual cycles and effectively preventing pregnancy are mutually exclusive. I reject this assumption as being true for all women, and assert that women have the right to succeed – or fail – using non-hormonal methods. The decision you have to make is whether you will help them succeed or just expect them to fail.

Hi Sara- I chose to abandon hormonal birth control when I was 21 due to side effects. My doctor suggested just trying yet ANOTHER hormonal method and when I expressed that I wished to never again be on hormonal contraception I was laughed right out of the doctor’s office.

What would you suggest to those “kids” that don’t wish to use hormonal contraception?

I’m still probably a kid in your eyes, at 24, effectively using FAM btw.

I’ll jump right into this energetic conversation! First, my perspective is influenced by: I had horrid health-destroying problems with a very high dose estrogen pill in the late 1960s lasting only five days! I volunteered for an IUD and even though I was willing to take the pain, it was not possible to insert it. From then on I only used a diaphragm with a full applicator of contraceptive jelly–I never had a miss. Most important of all, I believe that ovulatory menstrual cycles are women’s passport to present and future health. (Enough of that!)

First of all, I agree with Laura that contraception IS considered to be something prescribed by doctors, not something women and men do themselves.

I also agree that all women should ask their men partner (especially if plural) to wear a condom to prevent sexually transmitted infections.

Like some of you, thirdly, I am very glad to see that now IUDs are effective and possible for use by women who have not been pregnant, had a miscarriage or an abortion.

That means that IUDs now become available to a woman who choses them as very reliable, non-adherence based form of contraception that (unlike Depo-Provera or implants) will not interfere with normal, ovulatory cycles, and that (unlike estrogen) will not cause blood clot risks, suppress cyclic peak interest in sex, and put you at risk for pregnancy with missing one of the low dose pills.

In spite of the contraceptive “devise” propaganda that is so common as to be expected, wider IUD availability is progress for women’s health.

I read in Barbara Seamans’ book “Women and the Crisis in Sex Hormones” (1977)that before the advent of the pill, the diaphragm was considered to be the “queen of contraception.” When doctors took the time to ensure their patients knew how to insert the diaphragm properly, women used them consistently and effectively. Those days are long gone. Good luck finding a doc to fit one or a drug store that sells them. The irony is that, as I’ve mentioned many times, the most popular sexual role model of the last 15 years – Carrie Bradshaw from Sex and the City – used a diaphragm.

I agree that wider copper IUD availability, for women who can tolerate this method, is a good thing for women who don’t want to use hormonal methods, including the hormonal IUD. But now that we know about the connection between inflammation and heart disease, diabetes, cancer, Alzheimer’s, and osteoporosis, should we be concerned that long-term use of the copper IUD, which functions by setting up an inflammatory response in the uterus, might have negative health effects? I suggest that women have a blood test for C-reactive protein before insertion of an IUD, then six months post insertion to see if C-reactive protein levels increases. CRP is a measure of inflammation, and high levels are a risk factor for heart disease. I think it’s important to know if ongoing use of the copper IUD raises CRP significantly. It may vary from women to women, but could become a contra-indication for some.

Jerilynn, do your comments apply to both the copper IUD and the Mirena? I consider the side effects of the Mirena to be significantly more problematic, especially for some women. I am concerned about the Mirena interfering with the maturation of the reproductive system in young teenagers, as does the pill, patch and ring.

Wow. How does one respond to a contraceptive counselor who believes (all?) teenagers and 20-somethings are KIDS who can’t be expected to manage their lives “like adult women” and therefore should be steered to injections and implantables? Better that 24 year-old Kate answered this one from her 20-something perspective.

I think if IUD use has increased 600% since 2006 as a recent study stated that we can safely assume that increase has a lot to do with the introduction of the Mirena. I think also considering the impact of Mirena on menstruation – decreasing flow – that it is more likely to be given to teen girls than a copper IUD. When I read the ACOG report I read it as the Mirena and Implanon being recommended, with good reason I think.

Re: Meghan’s comment – “Why is it your place to tell a woman who does not feel she can ask her partner to use condoms that she should be using a barrier method, or periodic abstinence?”

I find it thoroughly disturbing that we can simultaneously validate, sweep under the rug and not deal with an issue like this – women not being able to talk to their partner about condoms and not being able to say no to sex -so easily with the promotion of LARCs. Because as long as she’s not getting pregnant this isn’t a problem? Are we saying that this woman Meghan refers to is simply choosing a “lifestyle choice” of being pressured by and not talking to her partner, rather than experiencing a serious problem that’s not just her own responsibility, but society’s responsibility?

This is the policy-sanctified attitude of population control advocates in the developing world. As they see it – those women get forced to have unprotected sex and do not have equal standing in their relationships so giving them a LARC solves that. Done. No need to deal with poverty or inequality because stopping the babies will fix that.

So, Meghan’s message here is – IUDs and implants are great because they let women get pressured into unwanted unprotected sex without having to worry about getting pregnant. YAY LARCs! I feel so empowered.

And what do you do when they come back to you asking to have the implant removed? Or if, after 6 weeks of horrible side effects from the injection they come back asking you when they will feel okay again? Discontinuation rates of LARCs are high – close to 50% have the implant removed or stop using the injection or have the Mirena taken out long before its due date is up. Then what? Do you refuse to take it out promising them that they don’t know what real suffering is like until they get pregnant?

You are quite right to raise the issue of inflammation about IUDs, Laura. There is local inflammation inside the uterus in those “wearing” an IUD. To put that into perspective, however, oral estrogen usually doubles the level of C-reactive protein and that includes the estrogen in the combined hormonal oral contraceptive. Just so folks know, it is not appropriate to order or ask for C-reactive protein levels to assess your risk for various problems–C-reactive protein is just not sufficiently sensitive or specific.

In answer to your question, I think that the Mirena (levonorgestrel-IUD) should probably be reserved as treatment for women with heavy bleeding. As you know, my first recommendations for heavy flow are ibuprofen and cyclic progesterone. Although the Mirena does not release much of the progestin into the blood stream, and it only minimally interferes with ovulation and menstrual cycle hormones, in most situations it is probably better to use a copper IUD (without hormones), especially in a teenager.

I’m not suggesting women themselves ask for a CRP test, just that it could be used as a tool to determine if IUDs contribute significantly to inflammation.

As Holly noted, it is much more likely that teenagers will be offered the Mirena than the copper IUD. I’d bet that reduced flow will be considered a major “benefit” and “selling point” in the presentation of the Mirena as one of the best LARC options to teenagers.

What I’m really concerned about is the new hormonal implant, IMPLANON (etonogestrel). I admit that I don’t know much about it, but based on the negative health impacts of Norplant, the previous implant on the market, and Depo-Provera, I’d be very hesitant to offer it to anyone.

Thank you for this fascinating discussion.

As I am offering a presentation to parents of students in a few of our county’s high school soon (entitled “Staying Connected to Your Hormonal Daughter”) I am particularly interested in the conversation about contraception and teens. My experience is that parents allow their fear of their daughters’ getting pregnant to override their concern for her endocrine health.

As I am also offering an 8 week group program for the teens to learn about their hormones, I am carefully considering how to address these parental concerns AND offer their daughters body literacy. I am afraid the parents’ fears will override their daughters receiving this information. Any thoughts and experience out there?

Also, I was not able to find your other post, Laura. The link kept coming back to this article. I would love to read it: “I expressed my concerns about pushing LARCs on teenagers in a previous re:Cycling post.”

Thanks again for a stimulating conversation.

Ashley, thanks for affirming what I’ve long considered to be a key issue: “My experience is that parents allow their fear of their daughters’ getting pregnant to override their concern for her endocrine health.”

I have serious concerns about girls being put on hormonal contraception for menstrual cycle “problems” that could be sorted out effectively in other ways without interrupting the maturation of their reproductive cycles.

My suggestions for parents would be twofold:

1)to explain alternate treatments for menstrual cycle pain, irregularity or heavy bleeding. Recommended take-away resources would included http://www.cemcor.ubc.ca.

2) to give their daughters Toni Weschler’s book Cycle Savvy: The Smart Teen’s Guide to the Mysteries of her Body (www.cyclesavvy.com) to ensure their daughters first acquire body literacy so that they fully understand how their bodies work before having to make decisions on how they will manage their fertility. Knowing how your body works can provide powerful self-knowledge and self-confidence. I like the idea of giving girls this book because the information – written expressly for them – eliminates the mediator of teacher or parent. Girls get to decide for themselves what this information means to them, and become partners in decision-making around their sexual and reproductive health.

Keep me posted on how you proceed with your program. You can always email me directly.

I fixed the link. It should be working now.